Math teacher, author, and competitor: Dennis Chen (‘23) publishes a geometry textbook

Dennis Chen (‘23) is currently working on reformatting his geometry textbook.

In sixth grade, bored in Spanish class, Dennis Chen (‘23) tried his hand at creating an original math problem. Involved in competition math since sixth grade AMCs (American Mathematics Competitions), Chen quickly realized that his simple math problem involved cyclic quadrilaterals, a topic that had long confused him.

“Not wanting to lose this sense of clarity, I tried re-deriving everything else about cyclic quadrilaterals…from basic principles. I learned that the inscribed angle theorem and cyclic quadrilaterals were one and the same…and that is something I think I would’ve found out much later if I didn’t write it down,” said Chen.

This process of writing things down and compiling notes began to spiral. Around fifty pages in, Chen began to recognize the implication of what he was doing—it was the beginning, however unlikely, of a full-blown textbook.

Formula for Success

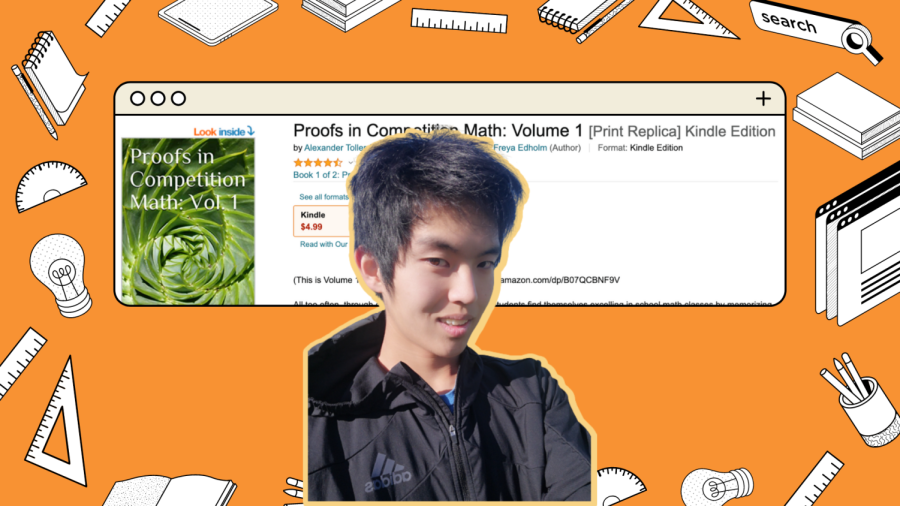

Currently, Chen has two textbooks under his name: “Proofs in Competition Math,” a published instruction book he co-authored, and a geometry textbook still in works, which he wrote individually.

Both textbooks had their roots in Chen’s preparation for mathematics competitions such as the AMC and AIME. The AMC and AIME are speed-dependent contests that require contestants to solve a problem as quickly as possible.

Training for both requires careful processing and critical thinking rather than mindless repetition. By writing and taking notes, one can better digest information and practice output, functions necessary in mathematics competitions.

One way to truly digest longhand information is to write a book.

Writing a book—a textbook, particularly—is no small task. Chen’s first draft spanned over two years in middle school, and even now he continues to revise and edit his work. According to Chen, there is an inevitable middle period of semi-clarity when writing a book, so the first draft is bound to be muddled or unclear.

“Acknowledge this, be aggressive about fixing it, and make sure that you can salvage what you have as easily as possible,” said Chen.

The technology used matters as well. For Chen, he prefers softwares like LaTeX (for print) and Markdown (for ebook).

LaTeXmost suited his work due to its ability to create appealing designs, randomize the order of problem hints and solutions, and produce reliable citations and bibliographies.

“When writing a book, you have a source and generate a PDF from it. If you’re doing things right, your book should be software. And if it’s software, you want the manipulation of the input—your text containing the content of the textbook—to be as flexible as possible, so that the output—the generated PDF—can be changed at ease,” said Chen.

The key to this “flexible software” is writing in plaintext, or text that is not written in code.

Put simply, in Chen’s words: “A textbook that isn’t written in plaintext is a textbook no one will ever care about.”

Behind the Math

Chen’s involvement with math doesn’t end at textbook writing. By teaching classes catered to students interested in AIME, an intermediate math competition bridging AMC 10 and AMC 12, Chen gradually improved his own curriculum.

“I was teaching classes here and there and collected my own—at the time, really immature and disjointed—curriculum. Soon I noticed that I cared more about the curriculum…than the actual lessons,” said Chen.

When his AIME classes came to an end, he devoted his attention to the curriculum. And when classes started up again, student interest ballooned. Twice as many students signed up than he’d originally planned for.

Of course, having more students was far from a bad thing. With 30-40 pages worth of material spread across eight handouts, Chen could use his expanded class as an opportunity to use and improve his own product: or to “dog food”, as is more technically known.

“There were a lot of eyes on it, student and staff combined, looking at every aspect that could be improved: a problem doesn’t fit here, a problem could be added there, [or] the design is awful,” said Chen.

Dennis Chen (‘23) is currently working on reformatting his geometry textbook.

Moving Forward

In sixth grade, Dennis took the AMCs for the first time. Two years later, he qualified for AIME (with 5,000 yearly qualifiers out of 500,000), and then for USAJMO in 9th grade.

This year, he qualified for USAMO, a highly selective mathematics competition with only 500 annual qualifiers.

“[In] the span of three years—from 6th grade to 9th grade—my performance improved by about two orders of magnitude. After working with some of the smartest students, I learned a lot about teaching and writing, and my standards for my own work rose even higher,” said Chen.

Some of his success, especially during his freshman year USAMO qualification, can be attributed to his work as a math textbook author.

“Only by writing the first draft did I really get good enough at geometry to make the USAMO in freshman year,” said Chen.

When writing a textbook, Chen suggests finding a legitimate publisher in order to hold yourself to a higher standard. While writing a textbook has obvious differences to fiction writing, the process itself has its similarities.

“Be ambitious. Maybe you will have to discard a large portion of your work, like I did,” said Chen.

Your donation will support the student journalists in the AVJournalism program. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

ebwarb • Jun 20, 2022 at 2:24 am

AWESOME ARTICLE !! Milla and Dennis are both such talented individuals